Our Virtues

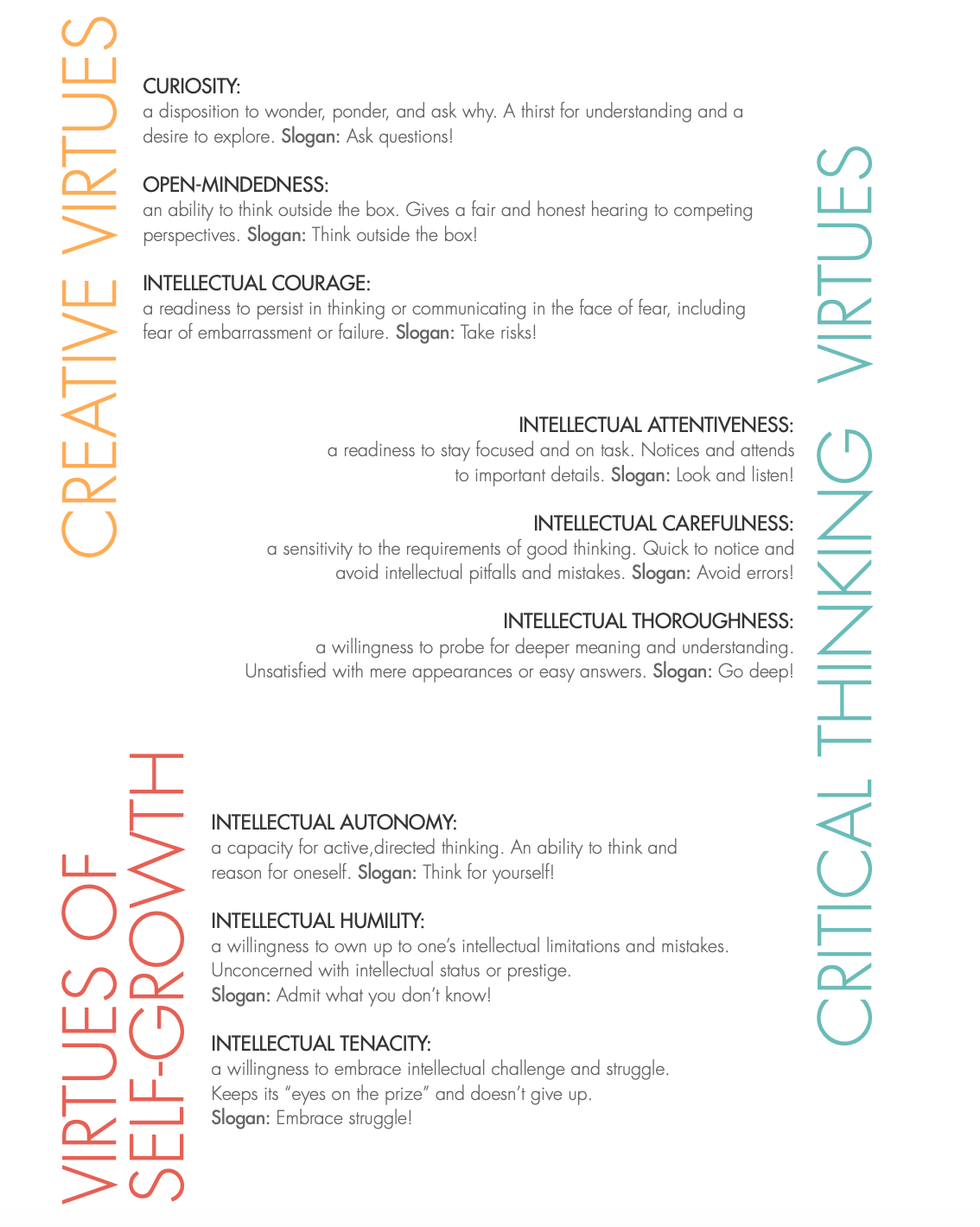

Creative Virtues

Critical Thinking Virtues

Self-Growth Virtues

Read More About Our Virtues

Intellectual Humility: A Researcher's Perspective

Created: Thursday, 11 June 2015 15:44

By Tenelle Porter, Post-Doctoral Researcher, University of California, Davis

It’s commencement season and last week I found myself listening to David Foster Wallace’s speech to Kenyon College graduates. He tells a story of two young fish that pass an older fish who is swimming in the opposite direction. The older fish says “Morning boys, how’s the water?” The young fish swim along for a while until one looks at the other and says “What the heck is water?” The point of the fish story, Wallace explains, is that we are often blind to the most obvious and important realities. Even more, lots of things that we are absolutely, automatically certain about turn out to be completely wrong. Research suggests Wallace is right. Lots of work in psychology shows that we routinely overestimate how much we know, that we have self-serving biases that distort our thinking, and that we are blind to our own bias (while holding fast to the belief that others are biased). This sounds like a bunch of...

Intellectual Tenacity

Created: Thursday, 04 April 2013 17:55

Written by Jason Baehr

How do you respond to challenge? In my own case, this tends to depend on what’s at stake. I’m quite willing to embrace challenge and work extremely hard if I care enough about the goal at issue. On the other hand, if I don’t see the goal as especially important, I tend to shy away from challenge. In other words, I don’t in general think of challenge as a good thing or as an opportunity for growth. This ambivalent attitude toward challenge illustrates some important points about trying to educate for growth in virtues like intellectual tenacity, perseverance, courage, and grit. These virtues have in common a willingness to embrace intellectual challenges or obstacles for the sake of some greater good. An intellectually tenacious person engages confronts and seeks to overcome these challenges instead of giving up or avoiding them. First, the ambivalence described above shows that as educators we should take significant pains to help our students understand the value of what we’re...

Intellectual Courage

Created: Thursday, 28 March 2013 22:34

Written by Jason Baehr We show courage when we are willing to suffer a potential loss or harm for the sake of some greater good—when we judge that a certain risk is worth taking. We show intellectual courage when we subject ourselves to a potential loss or harm in an intellectual context, for example, in the context of learning or in the pursuit of truth. One memorable example of intellectual courage is Edward R. Murrow’s famous World War II news broadcasts. Murrow subjected himself to harrowing conditions (conducting live broadcasts from London rooftops with German bombs raining down around him) for the sake of reaching the truth. He felt that the American public had a “right to know” what was happening during the war and he was willing, for a time, to place this right above his own well-being. If this is what intellectual courage looks like, what does it have to do with middle school education? In fact, intellectual courage wasn’t initially on IVA’s list of “master virtues.” However, as we reflected...

Open-mindedness

Created: Friday, 22 March 2013 04:51

Written by Jason Baehr As human beings, we love to be right—right in how we act, but also in what we believe. In principle, there’s nothing wrong with this desire. However, the desire to be right often has such a strong grip on us that we have a very difficult time handling it when someone disagrees with us or criticizes something we believe or have said. Our kneejerk response is to be defensive or to attack the person who has challenged us. One illustration of this is our susceptibility to what psychologists call “confirmation bias,” a pervasive human phenomenon whereby we unconsciously seek out evidence that supports our beliefs and ignore or distort evidence that doesn’t. Open-mindedness is a virtue that helps loosen the grip of our desire to be right. It frees us up to consider alternative views—even those that have been thrust upon us in a negative or critical spirit—in a way that is open, fair, and honest. It permits us to give opposing views or criticisms their due. A powerful illustration of...

INTELLECTUAL THOROUGHNESS

Created: Thursday, 14 March 2013 22:46

Written by Jason Baehr

Intellectual thoroughness is about going deep. An intellectually thorough person considers all the evidence, not just what is conveniently available. He double-checks his sources. And he considers multiple perspectives before making judgments. But, ultimately, intellectual thoroughness is about deep understanding. An intellectually thorough person isn’t content with surfacy knowledge. He likes to wrap his mind around important ideas, to grasp why, and to be able to explain what he knows. Teaching for deep understanding is a rare phenomenon in settings where scores on standardized exams and “teaching to the test” define the educational culture. Sadly, in settings like these, the opposite of intellectual thoroughness (intellectual hastiness, laziness, etc.) is the natural outcome. You might think that teaching for intellectual thoroughness by teaching for deep understanding would be off-putting to kids. They might regard it as simply involving more work. But what’s the alternative...

Attentiveness

Created: Monday, 11 March 2013 17:00

Written by Jason Baehr

It’s easy to think of an attentive student as one who always follows the teacher’s admonition to “pay attention!” But this is a very limited way of thinking about attentiveness. Understood as an intellectual virtue, attentiveness involves much more. Most significantly, it involves attending to subtle but important details. The attentive person notices things. She picks up on critical nuances of meaning. She registers the significance in what another person says. And she sees beyond mere appearances to the more important—or more beautiful, shocking, delightful, or sinister—details of the world around her. The attentive person also tends to be inquisitive. She asks questions about the things she attends to. In this respect, attentiveness is an extension of curiosity. It is curiosity expressed in how we direct our attention, what we focus on, what we give our minds to. The attentive person, like the curious person, has an engaged and inquiring mind. This point is illustrated nicely in...

INTELLECTUAL CAREFULNESS

Created: Thursday, 07 March 2013 21:48

Written by Jason Baehr

Intellectual carefulness is not the sexiest of virtues. And yet it is critically important. In fact, part of why it may be less alluring than, say, curiosity or intellectual tenacity is that the need for it is so familiar and pervasive. Intellectual carefulness involves an awareness of and responsiveness to important intellectual rules or requirements – including, perhaps most importantly, the requirements of good thinking. The careful thinker is alert to potential mistakes and errors and takes pains to avoid them. She desires to know—to understand—and therefore is slow to judge and quick to probe deeper. The far-reaching importance of intellectual carefulness is nicely described by author Phillip Dow in his forthcoming book Virtuous Minds: “Of course, few of us consciously rush to judgments in situations of such gravity. Yet in the so-called little things we are often guilty of habitually hasty thinking. How often, for instance, do we uncritically accept casual office gossip or...

Intellectual Humility

Created: Thursday, 21 February 2013 21:54

Written by Jason Baehr

The very idea of humility tends to elicit mixed reactions. Some equate it with spinelessness, servility, diffidence, and other undesirable traits. They think, for instance, of Winnie the Pooh’s Eeyore, or of the famous Dickens character Uriah Heep, who says of “umbleness”: “They taught us all a deal of umbleness – not much else that I know of, from morning to night. We was to be umble to this person, and umble to that; and to pull off our caps here, and to make bows there; and always to know our place, and abase ourselves before our betters.” But this is a far cry from genuine humility. Consider, by contrast, a person who is so comfortable in her own skin or has such a strong sense of self-worth that she can freely acknowledge her limits, struggles, and failures. She is not afraid of what other people think. She does not try to micro-manage their perceptions of her. Nor is she very concerned with status, pecking orders, or the like. She is free to be herself—so free that she can...

Intellectual Autonomy

Created: Thursday, 14 February 2013 21:57

Written by Jason Baehr

What’s your image of the ideal student? Many of us are likely to imagine a student who pays attention, listens quietly, completes all of his homework, scores well on exams, follows the rules, and so on. To be sure, these are some good intellectual behaviors. But notice that they are consistent with a complete absence of one very important intellectual virtue: intellectual autonomy. Intellectual autonomy is a willingness and ability to think for oneself. A person with this virtue is not overly dependent on others when it comes to forming her beliefs. She is not a mere receptacle for information and ideas deposited by others. In other words, her thought life is not primarily passive. It is active. The intellectually autonomous person is capable of forming her own judgments, initiating reflection, and asking probing questions. Of course, intellectual autonomy needs to be balanced and tempered by other virtues like intellectual humility and intellectual trust. We need to be aware and...

Curiosity

Created: Friday, 08 February 2013 04:07

Written by Jason Baehr

Curiosity isn’t always a good thing. It was curiosity that killed the cat, after all; and, if Curious George is any indication, it is very closely tied to mischief. But think of someone whose mind you admire. What are the qualities or characteristics of this person’s mind? Chances are that curiosity is among them. Curiosity can, then, be an admirable intellectual trait. It can be an intellectual virtue. Real learning begins and ends with curiosity. It is curiosity that causes us to ask questions, to wonder, to seek understanding. Just imagine what human civilization would be like if curiosity had never made an appearance—if people only sought the knowledge or understanding necessary for survival. There would no science, no technology, no art. There would be no real culture. What, then, are our schools doing to facilitate curiosity in students? Suppose you were to pull aside your son or daughter’s teacher and ask: “What specific activities, assignments, or teaching strategies do you...

.jpg?width=2700&height=900&name=IVAHigh_Logo_CMYK%20(1).jpg)